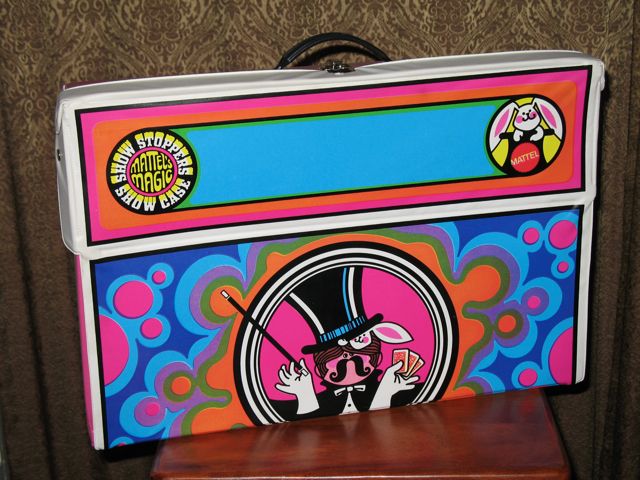

The Horror! The Horror! — that’s the title of a book I’ve recently enjoyed. The subtitle is: Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read. It’s a celebration of horror comics from the early 1950s, the most famous of which is EC’s Tales from the Crypt. But while the EC books are often written about and are currently back in print in hardcover collections, this book devotes most of its attention to the scores of all-but-forgotten titles that were published every month: Dark Mysteries, Uncanny Tales, Tomb of Terror, Diary of Horror, Chamber of Chills, Mister Mystery, Weird Terror, Menace, Horrific, Chilling Tales, Black Cat Mystery, The Thing, Out of the Shadows, and my favorite title, This Magazine is Haunted. In the heyday of horror comics, it was not uncommon for drugstores and news stands to have an entire wall devoted to these enticingly garish funnybooks, because they sold like crazy. Sadly, the entire enterprise was doomed, not by the whims of fate but by the comics publishers themselves, who rolled over for grandstanding politicians and social commentators who singled out horror comics as a scapegoat for any number of societal ills, including murder, theft, sexual deviancy, and dancing on sabbath days. (Well, maybe not that last one.) Bullied into submission, and fearing the specter of government regulation, in 1954 the comics industry established the self-censoring Comics Code Authority and effectively banned their bestselling product. The new rules forbade use of the words horror and terror in comic book titles. Also banned were vampires, depictions of unlawful activities that encouraged “sympathy for the criminal” or “distrust of the forces of law and justice,” and “scenes or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism.” And that’s just a tiny sample of the wackadoo regulations these folks were coerced into imposing on themselves. Nevertheless, it was all for the greater good, because from that day forward, Americans have been living in a crime-free utopia where gumdrops fall from the trees. But I digress.

The Horror! The Horror! — that’s the title of a book I’ve recently enjoyed. The subtitle is: Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You to Read. It’s a celebration of horror comics from the early 1950s, the most famous of which is EC’s Tales from the Crypt. But while the EC books are often written about and are currently back in print in hardcover collections, this book devotes most of its attention to the scores of all-but-forgotten titles that were published every month: Dark Mysteries, Uncanny Tales, Tomb of Terror, Diary of Horror, Chamber of Chills, Mister Mystery, Weird Terror, Menace, Horrific, Chilling Tales, Black Cat Mystery, The Thing, Out of the Shadows, and my favorite title, This Magazine is Haunted. In the heyday of horror comics, it was not uncommon for drugstores and news stands to have an entire wall devoted to these enticingly garish funnybooks, because they sold like crazy. Sadly, the entire enterprise was doomed, not by the whims of fate but by the comics publishers themselves, who rolled over for grandstanding politicians and social commentators who singled out horror comics as a scapegoat for any number of societal ills, including murder, theft, sexual deviancy, and dancing on sabbath days. (Well, maybe not that last one.) Bullied into submission, and fearing the specter of government regulation, in 1954 the comics industry established the self-censoring Comics Code Authority and effectively banned their bestselling product. The new rules forbade use of the words horror and terror in comic book titles. Also banned were vampires, depictions of unlawful activities that encouraged “sympathy for the criminal” or “distrust of the forces of law and justice,” and “scenes or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism.” And that’s just a tiny sample of the wackadoo regulations these folks were coerced into imposing on themselves. Nevertheless, it was all for the greater good, because from that day forward, Americans have been living in a crime-free utopia where gumdrops fall from the trees. But I digress.

The Horror! The Horror! is a fun collection of words and images. It’s great to read the more obscure stories that haven’t been reprinted before, and to see the amazing artwork, a significant portion of which was done as work-for-hire by uncredited artists. The publishers of this book went all-out on lavish full-color reproductions of these vintage comics covers and pages. And while the accompanying text by editor Jim Trombetta, who selected the comics included in this collection, tends to be more than a tad overheated — his interpretations of the subtext and themes of the stories and artwork are sometimes just as wacky as the projections of repressed “experts” from the 1950s — it does serve to place the work in a social context. And for an even better glimpse into the social climate of the day, the book comes with a delightful bonus feature: a thirty-minute DVD that contains an episode of the TV show Confidential File, which aired in October of 1955. The episode is dedicated to the “problem” of horror comics and their corrupting effect on the nation’s youth. It’s presented as hard-hitting reportage, of course, but it’s a trove of pure comedy gold. The lengths these people went to in the effort to prove that comic books were a danger to society are wonderfully ludicrous. You will laugh and shake your head in disbelief. The program is made even more absurd in light of the fact that the ban on horror comics was already in place by 1955. The arseheads who made Confidential File were trying to kick the last bit of drama out of a dead horse.

Here’s a link to the book on Amazon.com. At twenty dollars, it’s a bargain. http://www.amazon.com/Horror-Comic-Books-Government-Didnt/dp/0810955954/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1290442289&sr=8-1

Fans of this stuff should also seek out Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s, edited by Greg Sadowski. Like The Horror! The Horror!, this book puts the focus on the non-EC horror titles that flooded the stands every month. These are straight-up reprints of the best stories from those comics, complete and uninterrupted by modern commentary. (The book does include end notes about the artists, authors, and stories.) While there’s a bit of overlap between the two books, Four Color Fear has many more stories in it. It’s well worth getting if you’re into vintage horror comics and want to read the stories that haven’t been reprinted before. My favorites include “Green Horror,” which is the tale of a murderously jealous cactus — yes, you read that correctly — and “The Flapping Head,” which begins with the following words: “There was a night when the ancient castle harbored three presences no human would want to see! The first was death itself — the second a phantom fated for a grisly mission — and the third was the thing that became THE FLAPPING HEAD!”

Fans of this stuff should also seek out Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s, edited by Greg Sadowski. Like The Horror! The Horror!, this book puts the focus on the non-EC horror titles that flooded the stands every month. These are straight-up reprints of the best stories from those comics, complete and uninterrupted by modern commentary. (The book does include end notes about the artists, authors, and stories.) While there’s a bit of overlap between the two books, Four Color Fear has many more stories in it. It’s well worth getting if you’re into vintage horror comics and want to read the stories that haven’t been reprinted before. My favorites include “Green Horror,” which is the tale of a murderously jealous cactus — yes, you read that correctly — and “The Flapping Head,” which begins with the following words: “There was a night when the ancient castle harbored three presences no human would want to see! The first was death itself — the second a phantom fated for a grisly mission — and the third was the thing that became THE FLAPPING HEAD!”

There’s more than twenty dollars’ worth of fun in this book, so it’s a bargain too. Here’s a link: http://www.amazon.com/Four-Color-Fear-Forgotten-Horror/dp/1606993437/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1290552347&sr=8-1